Being a good designer entails possessing a comprehensive understanding of materials, encompassing both their theoretical underpinnings and practical applications. Materials play a pivotal role in my design practice, taking a central position in my creative process. The purpose of this article is to present a framework that delves into the practical aspects of learning from materials and explores how such an approach can enhance the outcome of a design. This framework has consistently proved invaluable to me when embarking on new design briefs or engaging in material experimentation. By adhering to this framework, I have been able to maintain focus, avoid haphazard approaches, and achieve more deliberate and purposeful design results.

Jean Prouvé working as an apprentice in 1917. Image: Centre Pompidou and Adagp via NY Times

Just like a chef would learn to cook using various ingredients and methods, the same applies to designers when learning to design with materials and fabrication techniques. Using a hands-on approach, I explore the methodology of building familiarity with a material and understanding the fabrication methods associated with said material.

A designer working with materials is like a chef working with ingredients. Image: Raimana Jones

A designer working with materials is like a chef working with ingredients. Image: Raimana Jones

Jean Prouve, known as an important figure in the world of design and architecture, is a great example that followed this methodology. Prouve was originally trained as a metal craftsman before becoming an internationally renowned furniture and architectural designer. It was the repetition of working with metal – the act of cutting, folding, bending, welding and forging metal that shaped his design vocabulary and style. "[...] tools and materials, if you know them well, can have an important effect on the form of the products." Prouve even says. Developing a proficiency with a material and its tooling processes will dictate the form.

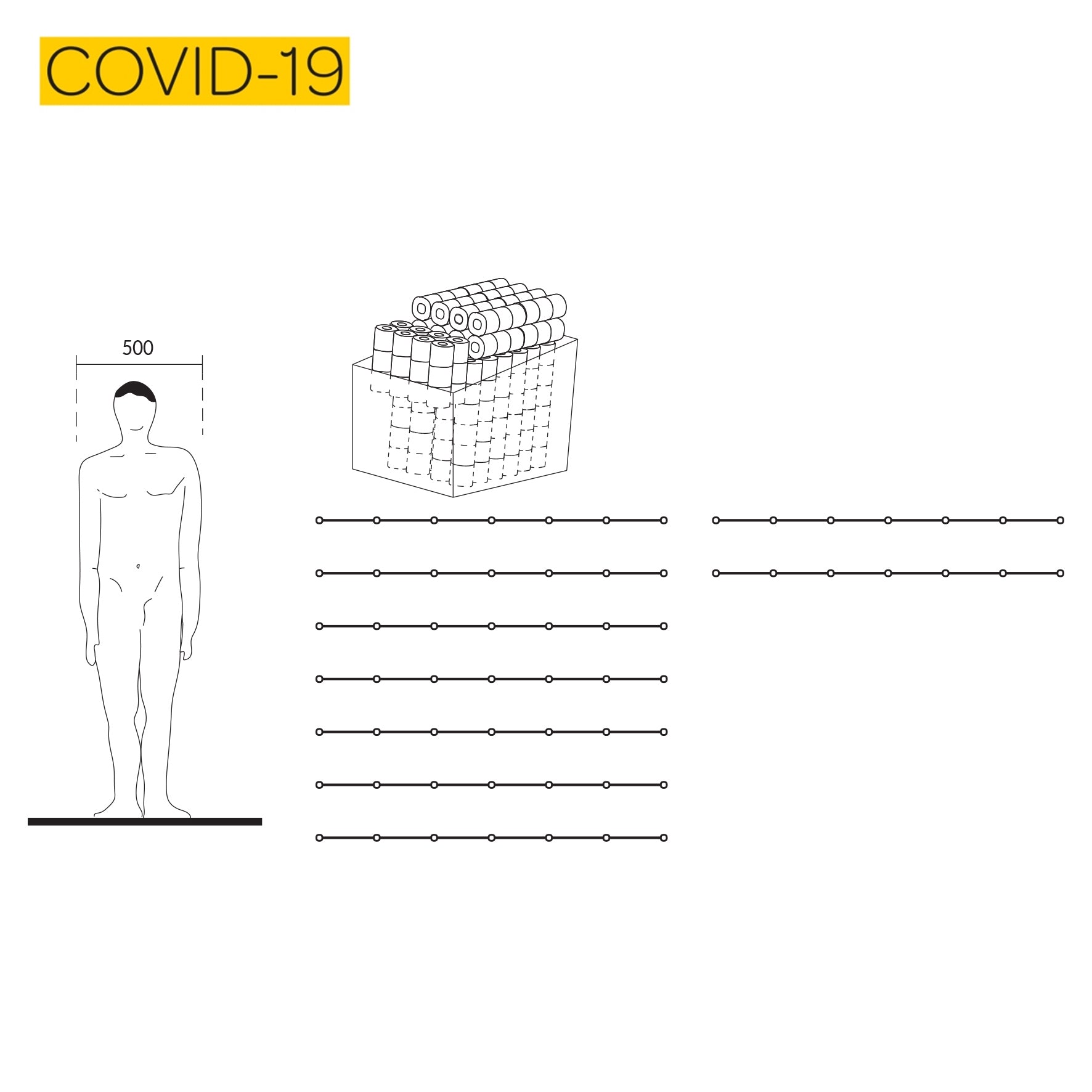

The starting point of this process is to identify the main tooling and main fabrication processes associated with a material of choice. Think of your material as an ingredient that you are trying to gain confidence with, as well as understand how and when to use it by identifying the different ways you can ‘cook’ with it. If we were a chef and took flour as an ingredient, the main cooking methods associated with it are: baking, thickening, and coating for frying.

The main cooking methods associated with flour. Image by Raimana Jones

If we chose steel, the main fabrication methods associated with it are welding, cutting, sheet folding, lathing and bending.

The main fabrication techniques associated with steel. Image by Raimana Jones

It is always good to start slightly broad and get an overview the different range of the tooling processes. The next step is to become more specialized by mastering two or three other techniques.

Jean Prouvé would cut then fold a steel sheet onto itself to increase its structural integrity. This, a signature technique of Prouvé, was used across the diverse range of his work, from his furniture to his building designs. This is a perfect example of how the use of a single material with a limited amount of tooling processes and techniques has formed a specialised design vocabulary.

Jean Prouve’s chair back leg tooling process. Image by Raimana Jones

The back legs of the chair and the metal girder is folded out of a single steel sheet – Jean Prouve’s signature technique. Image from the Patrick Seguin Collection

When it comes to a signature technique in relation to a material, Finnish architect and designer Alvaar Alto’s is another great example. Aalto, in collaboration with his wife, Aino Aalto, and furniture producer Otto Korhonen, developed furniture using bent wood and lamination techniques for large scale production.

Bent wood experimental model. Alvaar Alto. Image by the paustian house by jørn utzon via flickr

Alvaar and Aino experimented with the process of curving and laminating thin slats of wood. Some of their experimentations would draw from their furniture making and some were abstract and independent. This process amplifies the warmth and tactile quality of timber and has enriched Alvaar Aalto’s design vocabulary consequently naturally transcribed in some of his architecture.

Alvaar Aalto’s bending and laminating process. Image by Raimana Jones

The bending and layering process of behind Aalto’s stool. Image: Huonekalutehdas Korhonen, Mauno Mannelin, 1936, From the collection of: Alvar Aalto Foundation via Google Arts & Culture.

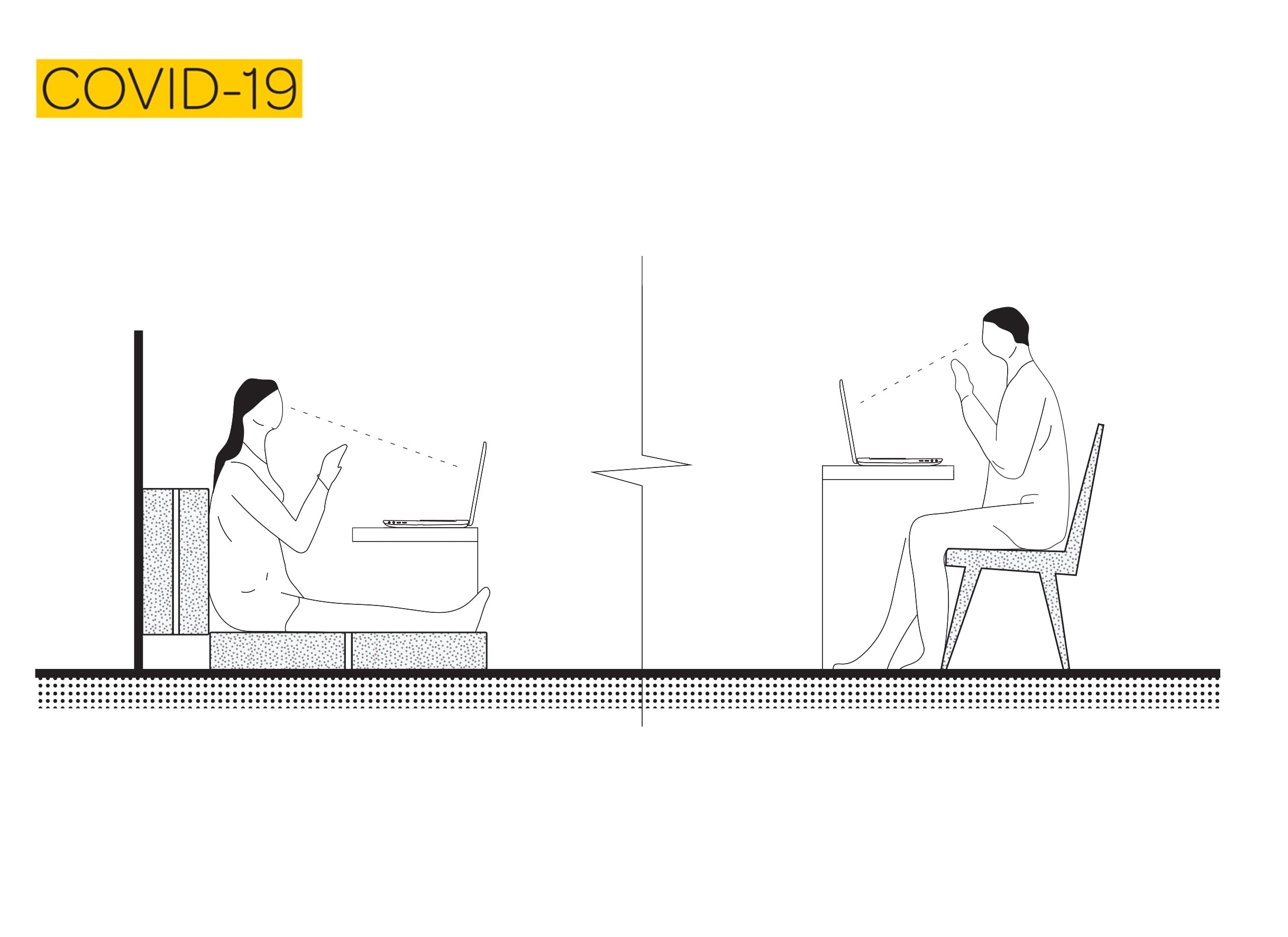

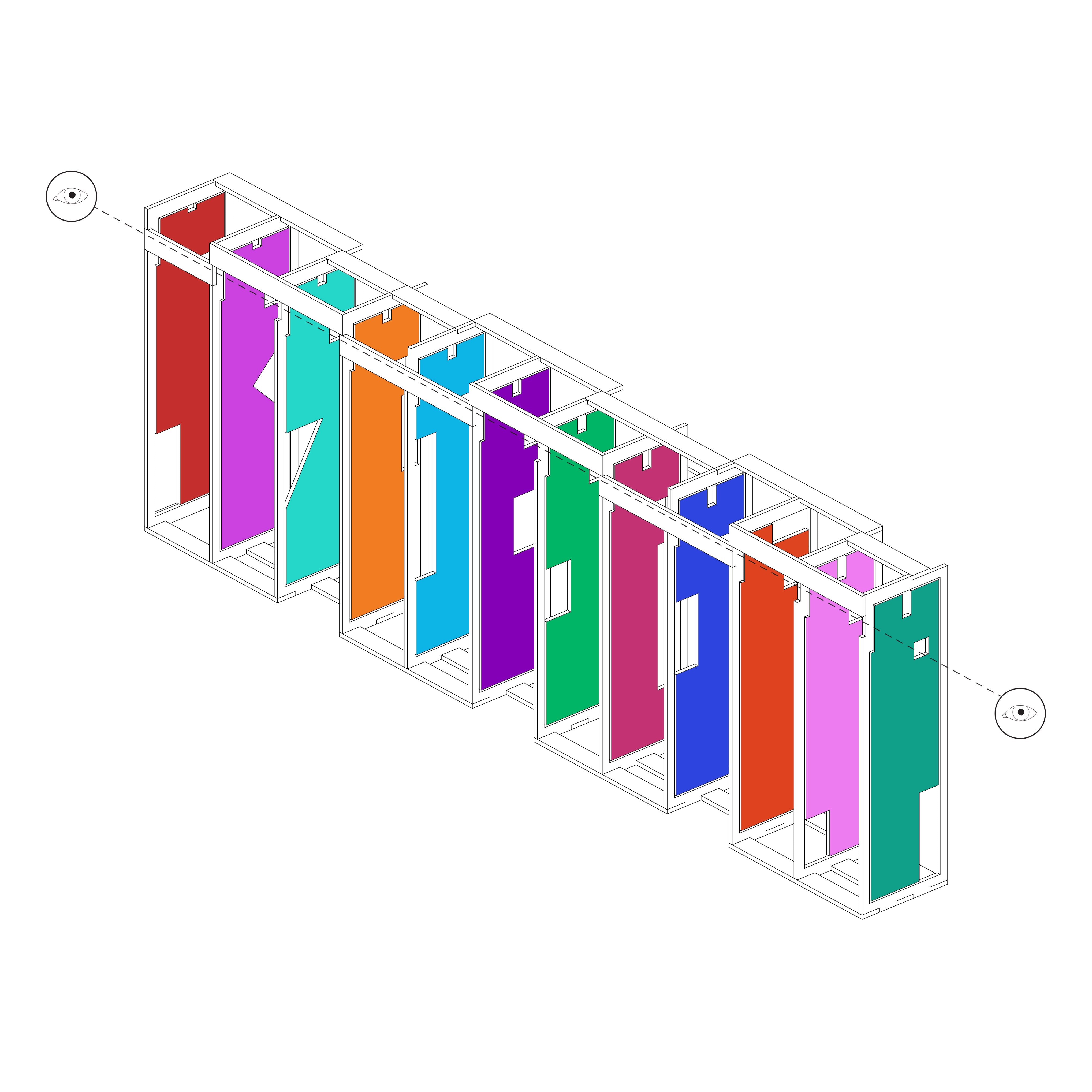

What these examples have in common is that the material familiarization and specialisation started at the scale of furniture and then progressed into the architectural scale. It suggests that keeping the scope of a material investigation fairly focused. i.e. one material along with a limited amount of tooling processes and starting at a small scale (furniture scale) would yield an enriched design vocabulary.

The Digital & The Hand

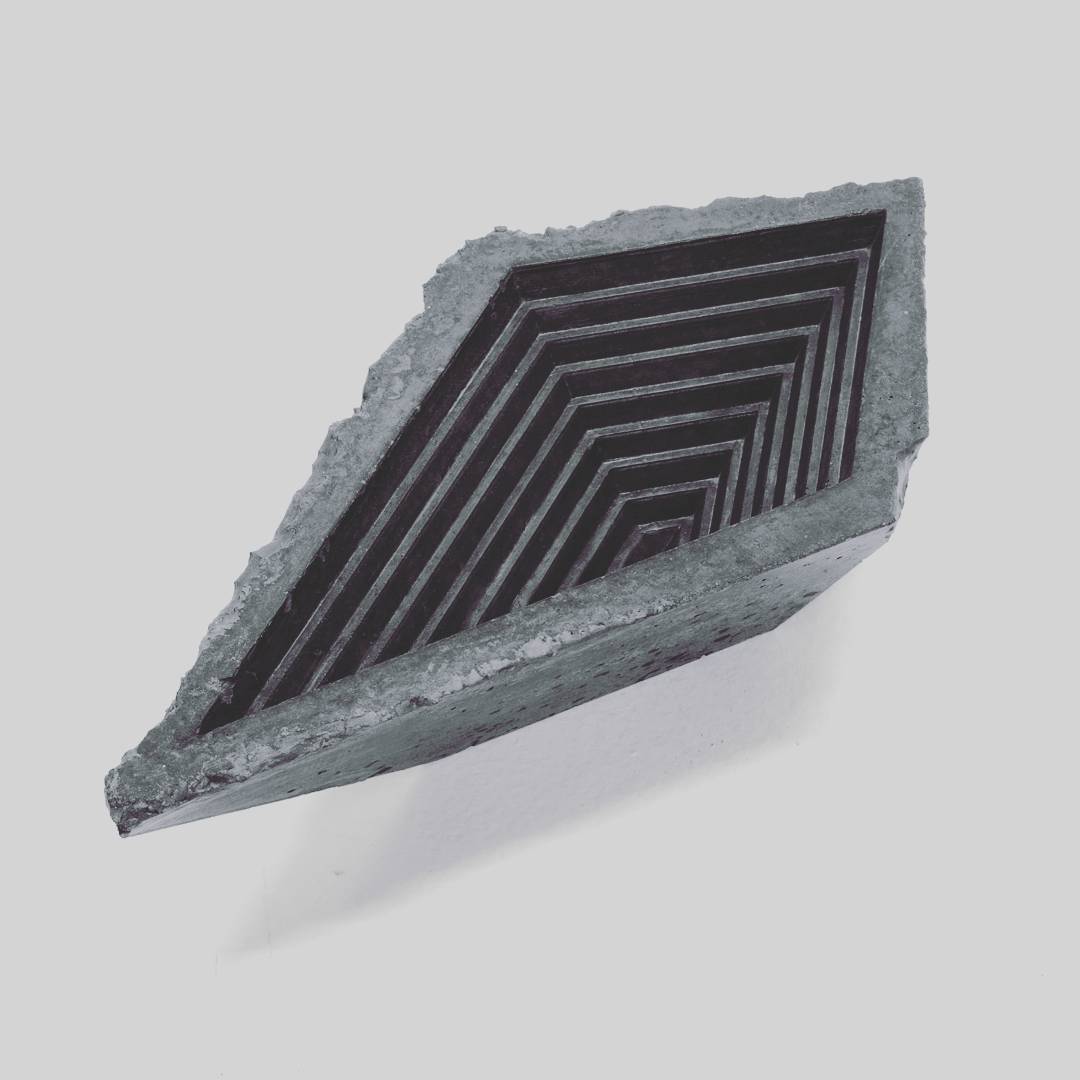

In this day and age, computer aided tools, also known as digital fabrication, have expanded the fields of tooling processes and fabrication techniques - adding precision, speed and pushing limitation of materials in completely new directions. Digital fabrication has also replaced traditional methods of working with materials. Carving and shaping wood through chiseling and spokeshaving is replaced by 3 and 5 axis CNC routing. This can remove important elements in the learning process and reduce the connection with the material. Starting from the traditional, the hand made and gaining a sense of ownership of the material is generally good practice before jumping onto computer-aided processes.

Dominion Road Tablet. Ceramic laser etched plate. Image by Benny Butcher

The new generation of designers and makers combine the best of both worlds: an in-between the analogue and the digital – a form of hybridized making. It reflects the progressive technology of our era and reminds us of our humanity.

A designer working with materials is like a chef working with ingredients. Image: Raimana Jones

A designer working with materials is like a chef working with ingredients. Image: Raimana Jones